Date: End of the 3rd century AD

Date: End of the 3rd century AD

Vessel: Roman merchantman

Cargo: amphoras, vaulting tibes, tableware, possibly grain

Depth: 94 meters

Origin: North Africa

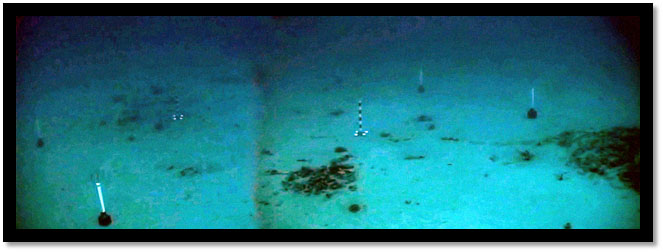

During anomaly verification in 2006, an E-W oriented wrecksite (SI06-AA), approximately 18 x 6 m in dimension, was discovered on a flat sandy stretch of seafloor at a depth of 94 m. It was comprised of ceramics, concretions, and possibly hull timbers. Located among the loose ceramic material is a distinctly square-shaped deposit of about one-square meter in size, that is comprised of large African amphora sherds, a few pieces of tableware, and over 100 tubi fittili (or vaulting tubes) visible on the surface.

From 2006-2009, the project proceeded to experiment with mapping, recovery, and excavation methods on the Levanzo I wrecksite. Several factors make the Levanzo I site ideal for experimentation with the mapping and excavation of sites via a ROV. It is clear based on the history of fishing in this area and the observed damage by drag nets that the Levanzo I wrecksite has been severely impacted. As much as 90% or more of the original deposit was removed years ago by drag-nets. Given the high degree of site disturbance from drag-net incursions and biogenic modification, it is unlikely that the current positions of many of the artifacts are congruent with their original depositional locations.

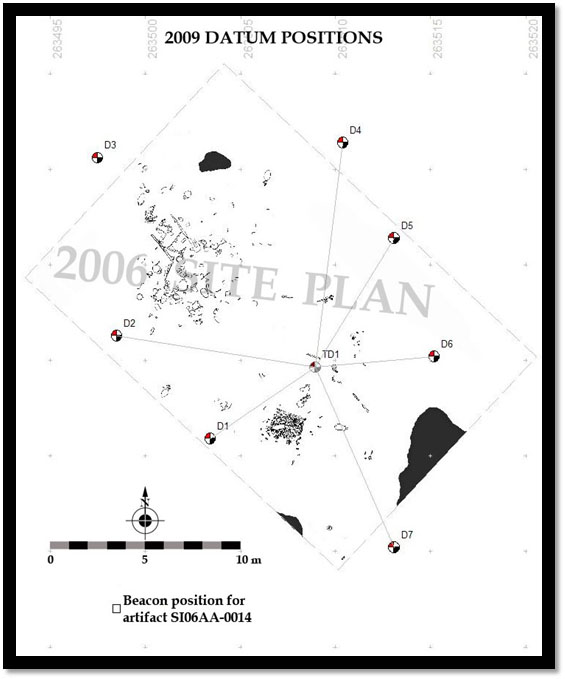

Although largely disturbed, it was decided to make every effort in designing and implementing a methodology to control and record the provenience of artifacts. As such, the primary goal was to conduct thorough and accurate site mapping. The overall stratagem was to control x and y because of their greater scale and importance on a site that is primarily comprised of surface finds. Given the tools available, the initial step was to place datums constructed of 10-cm diameter pvc pipe encased in a block cement around the site in order to provide reference points for measuring. Each of these datums was 1 m in total height. It was envisioned from the beginning that one of the methods for determining the positions of the datums, and thus objects on the site, was to measure in the datums relative to one another utilizing Site Recorder software.

Amphoras

This site represents a Roman merchantman laden with food stuffs and construction materials that was en-route from N Africa to the Italian mainland when it met its demise at the end of the 3rd century AD. Easily-identifiable amphoras were left in situ, while several pieces of tableware and four vaulting tubes on the surface were raised for analysis and identification. Tableware was a common find; Among the tableware items collected were a coarseware plate, flagon, and small table amphora. The variety, distribution on the site, and representative amount indicate this was part of the cargo; moreover, the presence of five flagons is a highly unlikely component of shipboard galley items. Coarseware from N. Africa was a common export item, particularly to Hispania, but was also shipped into Central Mediterranean ports. Such items were commonly tertiary goods associated with government shipments and loaded onboard with state cargoes by captains endeavoring to make additional earnings.

Amphora types visible on the surface included African 2B, African 2D, Riley MRA1, Almagro 51C, Ostia 1 – 455, and Dressel 30-Mauritanian. Likewise, the majority of the types identifiable on the site have a Tunisian production area. The variety of amphoras on the site’s surface have circulation dates that overlap the end of the 3rd century CE and combined with the great number of large cylindrical body sherds on site indicate a N African origin of the cargo. Food stuffs contained in these amphoras were likely wine and fish products.

The majority of these were amphoras noted in the imagery from other seasons, which necessitated recovery for a more confident identification. Direct analysis confirmed the general assessments, for the most part, of the amphoras in that the primary mix is mostly N. African (Africa), and most likely Tunisia, in origin with a secondary presence of cargo from Portugal (Lusitania). A lesser representation originates from the East Mediterranean/Black Sea. All examples have an overlapping date in the 4th century CE; however, the little is known of the Troesmis XIII type and its extension into the 4th century CE may be a contribution of this site.The general assemblage is consistent with that one would imagine working the main trunk routes of the annona trade, particularly that between Carthage and Rome. The presence of amphoras from Portugal and further east speak to the importance and magnitude of Carthage as an entrepôt. The absence of amphora material from the central portion of the wrecksite, confirmed in the test excavations, substantiates the theory that this vessel was carrying grain as part of its cargo. Grain would have been a common item on board, along with the oil and fish products indicated by the amphoras.

The majority of these were amphoras noted in the imagery from other seasons, which necessitated recovery for a more confident identification. Direct analysis confirmed the general assessments, for the most part, of the amphoras in that the primary mix is mostly N. African (Africa), and most likely Tunisia, in origin with a secondary presence of cargo from Portugal (Lusitania). A lesser representation originates from the East Mediterranean/Black Sea. All examples have an overlapping date in the 4th century CE; however, the little is known of the Troesmis XIII type and its extension into the 4th century CE may be a contribution of this site.The general assemblage is consistent with that one would imagine working the main trunk routes of the annona trade, particularly that between Carthage and Rome. The presence of amphoras from Portugal and further east speak to the importance and magnitude of Carthage as an entrepôt. The absence of amphora material from the central portion of the wrecksite, confirmed in the test excavations, substantiates the theory that this vessel was carrying grain as part of its cargo. Grain would have been a common item on board, along with the oil and fish products indicated by the amphoras.

The interesting aspect for study within this assemblage are the Riley 1B amphoras that thus far have an uncertain production area. With this vessel hailing from Tunisia and a high representation of this type in the remaining cargo, these finds may support arguments for a N. African origin. A further analysis of each type, their distribution on the site, and where these fit into the original cargo will be addressed in the publication of the site.

Vaulting Tubes

Another intriguing element of the cargo was the consignment of vaulting tubes. Such tubes were used in the initial formation of arches or vaults; after forming an acceptable shape, they were taken down and reassembled with a light mortar. Afterwards, concrete was poured over the form and the interior was covered with plaster. Four tubes were collected for recording and analysis, each of these located just off the side of the square deposit on the eastern portion of the site.

Glass

Several glass fragments have been found on the site. At least two of the fragments represent two different vessels: possibly a square bottle and a plate. All fragments were clear (presumably colored with manganese oxide) and appear to be mold blown. Such glass is consistent with the 4th century date of the wreck. The presence of this glass underscores the presence of secondary items shipped along with annona cargoes.

Fasteners

Ship’s fasteners were also a common find. Each of these fasteners were nails, and 6 of the 10 were found within amphoras. Undoubtedly chunks of wood were pulled in by octopi with nails inside and rotted to leave the nails behind. All nails were square in cross-section and possessed a blue-green color where the black patina was missing that indicates they were made of a probable copper, or copper alloy, material. Furthermore, each of the nails’ heads were rounded squares from a top view, and appear to be bent downwards towards the shaft. As a result, there is a square-shaped, flat crown on the heads. Note that there is little consistency in the length of the nails, ranging from 2.7-14.5, yet more consistency in their shaft widths.

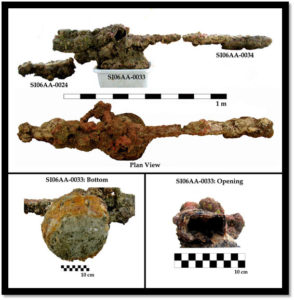

Concretions

A large concretion found is comprised of at least two iron bars, square in cross section, with a large ball attached about midway along its length. The most horizontally linear bar appears nearly intact, whereas another bar crossing this one appears to have lost part of its length that would have extended upwards. There appears to be wood included within this concretion, particularly the majority of concretion SI06AA-0024. A nail hole (0.7 square) and a large bolt head (2.5 high, 3.2 diameter) in the upper portion of this concretion confirms the presence of a large timber. This nail hole is consistent in shape and dimension to those nails found on the site.

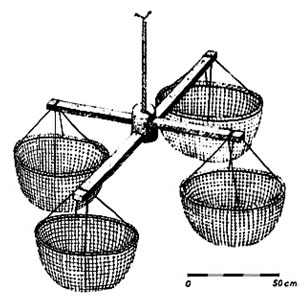

Without an analysis of this concretion completed, it is almost impossible to determine what the object may have been that created it. However, there are parallels from other Roman-era discoveries that may assist in guiding the conservation and analysis. Fish traps made of crossed iron bars and chain could produce this deposit, such as the one from the Cassidaigne deposit (Benoit 1962, p. 12, Fig. 43-44; found in the mouth of Rhone that contained material from 3rd BCE-5th CE). The basic dimensions of the trap and its configuration are similar to the combined concretion recovered. If this were a version of the fish trap, the baskets on the Levanzo I wreck may have been nested, the chain wrapped with them, and placed with the two iron cross bars for storage. The baskets themselves were likely made from cord and have since rotted away, leaving the ball of chain in a concreted mass. Likewise, this may be ships equipment or a part of the cargo consignment. An x-ray or other examination of this concretion should allow the definition of an object that will provide interesting insights into this wreck.

Without an analysis of this concretion completed, it is almost impossible to determine what the object may have been that created it. However, there are parallels from other Roman-era discoveries that may assist in guiding the conservation and analysis. Fish traps made of crossed iron bars and chain could produce this deposit, such as the one from the Cassidaigne deposit (Benoit 1962, p. 12, Fig. 43-44; found in the mouth of Rhone that contained material from 3rd BCE-5th CE). The basic dimensions of the trap and its configuration are similar to the combined concretion recovered. If this were a version of the fish trap, the baskets on the Levanzo I wreck may have been nested, the chain wrapped with them, and placed with the two iron cross bars for storage. The baskets themselves were likely made from cord and have since rotted away, leaving the ball of chain in a concreted mass. Likewise, this may be ships equipment or a part of the cargo consignment. An x-ray or other examination of this concretion should allow the definition of an object that will provide interesting insights into this wreck.

Conclusion

The Levanzo I wreck offers other important contributions towards the questions of exchange and redistribution during the late 3rd century CE as well as the dissemination of architectural technology. Direct evidence for the heavy shipment of goods from N Africa to Rome-Ostia during the Imperial period has been well established through amphora finds in Rome and Ostia. This trade and redistribution were part of the annona system. The major foodstuffs carried along this particular route were wine, oil, grain, and fish products. There was a rise in N African imports to Rome in the 3rd century, and after a split in annona supply by Constantine, N African supply sources overwhelming dominated Rome-Ostia imports throughout the 4th century CE. The Levanzo I wreck’s cargo of wine and fish products has a N African provenience, and the conspicuous lack of remains in the center of the site may indicate that grain was part of its cargo.

Such a cargo mix, and its route from N Africa towards the central region of western Italy, indicates this vessel was possibly engaged in an annona shipment at the time of its sinking. When engaged in service for the annona, ship’s captains often included additional cargos such as coarsewares, finewares, and architectural materials in order to realize greater personal profits on these ventures. Tubi Fittili are not known to be part of annona shipments, but would be a logical personal cargo item.

Continued excavation and analysis of the Levanzo I site will help to address several research questions. Are there amphoras from other regions or of different types in the cargo? How large is the deposit of tubi fittili and are there other concentrations on the site? Is there direct evidence for grain as a cargo item? The removal of sand cover, collection and analysis of artifacts, and taking of sediment samples in future seasons will hopefully aide in answering these questions.