The site of a major naval battle between Roman and Carthage during the First Punic War; the first ancient naval battlegrounds to be found by archaeologists

Egadi 11 Ram

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

The evidence from all sources falls short of what is needed for a complete description of the ships; for although our information on certain points is ample and conclusive, there are many points on which we have no information whatever. Practically, this is not a matter of importance, as nobody is likely to resuscitate the ancient style of shipbuilding in its entirety; and hitherto no attention has been given to the devices that might still be serviceable. (Torr 1895, ix)

Read More The study and expertise of the archaeologist, and particularly maritime archaeologists, includes the methods of construction, types of material, and performance characteristics associated with ancient sea-going vessels. Direct examination of ancient hull timbers provides a unique analytical perspective for maritime archaeologists. Moreover, the first-hand interaction with ancient wrecksites also provides distinctive knowledge concerning the utilization of, and depositional environments for, ancient vessels. The nature of the material culture and its assessment by archaeologists can address questions different from those dealt with by historians. Once archaeologically-based hypotheses are formed, it is possible to then create a dialogue with those based on historical and iconographic evidence. Implicit within the archaeological study of warships and rams is a hierarchy of evidence in the formation of hypotheses. This hierarchy is: The second trend was the advent of maritime archaeology beginning in the 1960s that over the course of several decades provided a solid understanding of ancient ship construction based on direct archaeological evidence. All of the evidence for ancient ship construction in the Mediterranean was derived from the analysis of merchant vessels. It was not until 1980 that the first direct evidence for ancient warships came to light, the Athlit Ram. Steffy (1991) was able to apply his intimate knowledge of ancient ship construction to the timber remains of the Athit warship and thus ushered archaeologists’ into the study of ancient warships. While ancient historians continued to build layer upon layer of hypotheses on what was increasingly iconographic and literary sources, archaeologists were forced to await supplementary direct evidence for ancient warships in order to further their lines of inquiry. Additional indirect archaeological evidence was investigated at this time, such as the Actium War Memorial by Murray (Murray and Petsas 1989) and Blackman’s (1982, 1987, 1991, 1995) work on ancient shipsheds. With the discovery of the Battle of the Egadi Islands archaeological new direct archaeological evidence was provided. Additionally, there was the serendipitous find of the Acqualodroni ram in 2008 off NE Sicily. The numerous rams and associated artifacts discovered with the Egadi rams is providing a wide variety of data for archaeologists to pursue the investigation of ancient warships. Archaeologists are now forming new hypotheses about the construction and nature of ancient warships that are often independent of those proffered by ancient historians and classicists. For the archaeologists, the hierarchy of data is quite different and yet more consistent with the earlier tradition: direct archaeological evidence, indirect archaeological evidence, inscriptions, followed by literary references and finally iconography. Armed with new direct evidence for ship construction, operations, deposition, and use of materials, our understanding of ancient warships will become clearer. > Read Less The objective of ancient warship study through archaeological evidence is not to test hypotheses based on written and iconographic evidence developed by historians. Rather it is compulsory upon archaeologists to assess the material culture associated with ancient warships, from which separate hypotheses will emerge.

The objective of ancient warship study through archaeological evidence is not to test hypotheses based on written and iconographic evidence developed by historians. Rather it is compulsory upon archaeologists to assess the material culture associated with ancient warships, from which separate hypotheses will emerge.

Hierarchy of Evidence

Moreover, the ordered nature of the list reflects only the relative rank of evidence types, but does not reflect the full qualitative differential. For example, the ‘gap’ if you will between Direct and Indirect Archaeological Evidence is far less than the gap between Historical Accounts and Iconography. Scholars have wrestled with the design, construction, and operation of ancient warships since the middle ages. Arguments for the nature of ancient warships played out in early scholarly journals of the 19th century. However, the data available to the scholars of these earlier periods was limited to inscriptions, literary references and iconography; no direct archaeological data was available. As such these early scholars were ancient historians and classicists, while archaeologists were largely on the sidelines. In 1895, Torr published a comprehensive article on the subject as it stood at the time and included a hierarchy of the evidence he used: inscriptions at the forefront, then statements by ancient authors, followed by the remains of docks and shipsheds, and lastly artistic works. Another prominent work by Torr in 1905 essentially followed this hierarchy of available data. Over the course of the 20th century two major trends were taking place. First, the ancient historians and classicists were gradually turning this hierarchy of data on its head and establishing more of their arguments on a foundation of iconography and artistic works.

Moreover, the ordered nature of the list reflects only the relative rank of evidence types, but does not reflect the full qualitative differential. For example, the ‘gap’ if you will between Direct and Indirect Archaeological Evidence is far less than the gap between Historical Accounts and Iconography. Scholars have wrestled with the design, construction, and operation of ancient warships since the middle ages. Arguments for the nature of ancient warships played out in early scholarly journals of the 19th century. However, the data available to the scholars of these earlier periods was limited to inscriptions, literary references and iconography; no direct archaeological data was available. As such these early scholars were ancient historians and classicists, while archaeologists were largely on the sidelines. In 1895, Torr published a comprehensive article on the subject as it stood at the time and included a hierarchy of the evidence he used: inscriptions at the forefront, then statements by ancient authors, followed by the remains of docks and shipsheds, and lastly artistic works. Another prominent work by Torr in 1905 essentially followed this hierarchy of available data. Over the course of the 20th century two major trends were taking place. First, the ancient historians and classicists were gradually turning this hierarchy of data on its head and establishing more of their arguments on a foundation of iconography and artistic works.The Effect of Direct Evidence on Maritime Archaeology

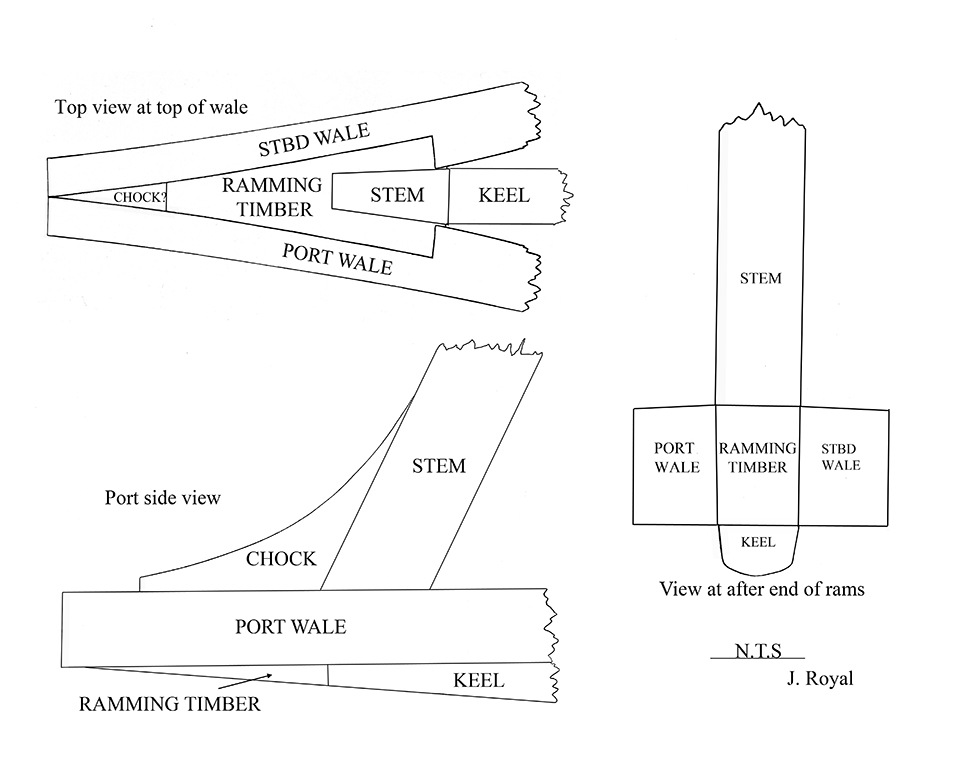

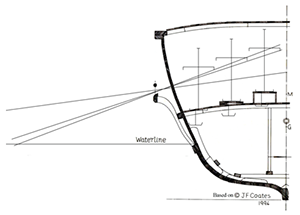

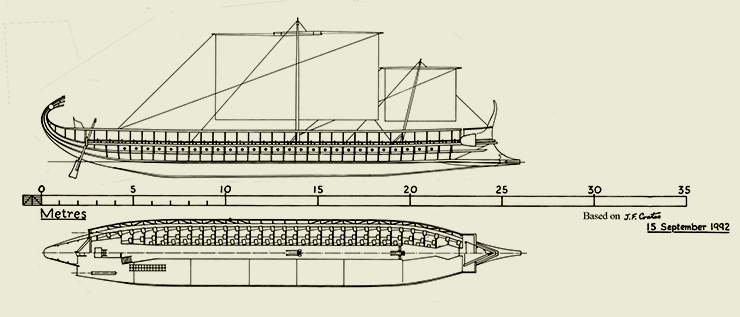

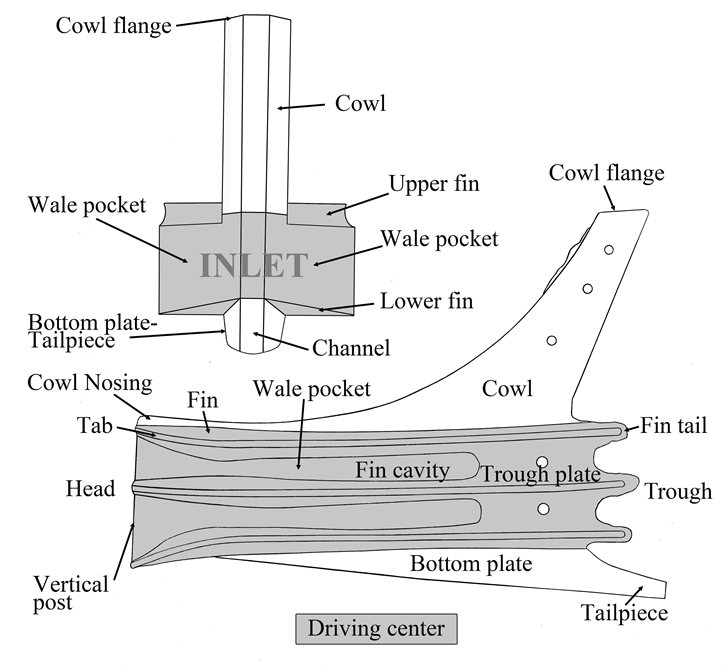

Read More The bow of a warship, like any ship, is exceptionally useful in understanding the overall hull construction. Obviously without direct evidence from the stern it is impossible to make statements with certainty about its configuration, and a it is not possible to directly determine the shape at the turn of the bilge. However, the major structural timbers for which there is direct evidence will dictate parameters for overall vessel length and for the shape of the hull at its forward end. Wood has certain properties as a construction material that includes various shear and compression strengths, as well as flexibility in relation to thickness and shape. Measurements from the internal cavities of the Egadi rams provide the cross-sectional dimensions and shapes for the main structural timbers: keel, stem, and waterline wales. Below you can see the bow timber configuration for the Egadi warships. > Read LessEvidence From the Bow

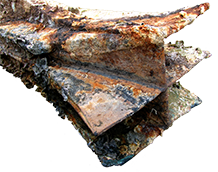

Based on the direct archaeological evidence some of the Egadi warships sank during the battle, suffered a great amount of degradation, and left debris on the seafloor. Analysis of the rams indicates, like all other rams, they were cast onto a specific warship bow; as such they offer a cast of the bow timbers from just behind the stem forward through the ramming timber.

Based on the direct archaeological evidence some of the Egadi warships sank during the battle, suffered a great amount of degradation, and left debris on the seafloor. Analysis of the rams indicates, like all other rams, they were cast onto a specific warship bow; as such they offer a cast of the bow timbers from just behind the stem forward through the ramming timber.

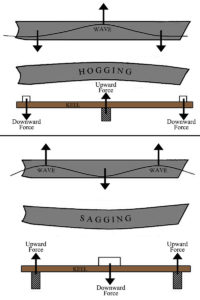

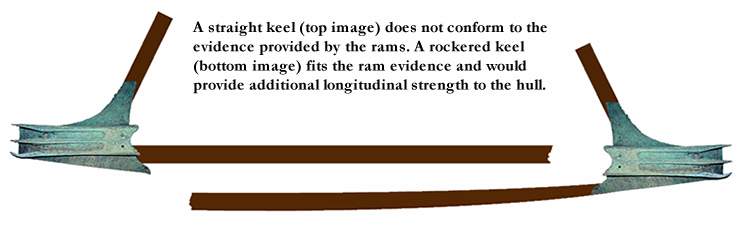

The dimensions of the keel are derived from the point aft of the stem, where the keel must have possessed its typical dimensions in order to maintain the hull’s structural integrity. Based on the cross-sectional dimension of the Egadi warships’ keels, they were closer to the size of the small Kyrenia merchantman and even the larger Athlit warship did not reach the dimensions of the 37-m Madrague de Giens merchantman. The Egadi warships were threes, wheras the Athlit warship is thought to have been a four. Robust keels were even more critical for vessels with high length-to-beam coefficients (warships) as they are more susceptible to hogging and sagging forces. Rounded merchantman hulls had length-to-beam coefficients of around 3:1, which created a near dome – a shape extremely resistant to hogging and sagging forces. However, elongated warship hulls had a much less effective shape. The bottom plates of the Egadi rams indicate the keels must have been rockered on these warships; such a design would be a logical measure to provide greater longitudinal support and resist hogging and sagging forces. Even rockered, the keels overall cross-sectional dimensions indicate the Egadi warships could not have supported a hull of 40-m in length as is often hypothesized for threes, rather on the order of 27 m in length.

The dimensions of the keel are derived from the point aft of the stem, where the keel must have possessed its typical dimensions in order to maintain the hull’s structural integrity. Based on the cross-sectional dimension of the Egadi warships’ keels, they were closer to the size of the small Kyrenia merchantman and even the larger Athlit warship did not reach the dimensions of the 37-m Madrague de Giens merchantman. The Egadi warships were threes, wheras the Athlit warship is thought to have been a four. Robust keels were even more critical for vessels with high length-to-beam coefficients (warships) as they are more susceptible to hogging and sagging forces. Rounded merchantman hulls had length-to-beam coefficients of around 3:1, which created a near dome – a shape extremely resistant to hogging and sagging forces. However, elongated warship hulls had a much less effective shape. The bottom plates of the Egadi rams indicate the keels must have been rockered on these warships; such a design would be a logical measure to provide greater longitudinal support and resist hogging and sagging forces. Even rockered, the keels overall cross-sectional dimensions indicate the Egadi warships could not have supported a hull of 40-m in length as is often hypothesized for threes, rather on the order of 27 m in length.

Have extensive dataset of ancient hulls, techniques for building, materials used. based on comparative construction mortise-and-tenon hulls, frames attached to planks and some to frames; attachment evidence – have spikes typical of frame-keel and frame-plank attachments, to smaller ones that appear to be for non-structural attachment such as ceiling planking, benches, or perhaps outriggers. Hulls of approx. 27 m in length would indicate warships of approx. 4 m in beam and a draft of approx. 2.5 m. Unlike the hypothesized threes such as the Olympias, these vessels would fit in the shipsheds, indirect evidence, that are contemporaneous with the Egadi warships. The size of the Egadi warships precludes there having superimposed tiers of rowing stations as is hypothesized for threes in the 5th century BCE. Given the freeboard and necessity for sailing, the Egadi threes had a single bank of oars that likely passed through outriggers. If the number of individuals on board threes of the 3rd century BCE included 170 rowers, although there are no direct statements for his in the historical evidence, and that the warships’ sized dictated a single bank of oars, then there were multiple oarsmen per oar. With the ability to model warships in computer programs that take into account the properties of wood and effects of waves, we can learn even more about construction and operations. Such a project is now underway through student research at the Maritime Studies Program, East Carolina University.

Given the freeboard and necessity for sailing, the Egadi threes had a single bank of oars that likely passed through outriggers. If the number of individuals on board threes of the 3rd century BCE included 170 rowers, although there are no direct statements for his in the historical evidence, and that the warships’ sized dictated a single bank of oars, then there were multiple oarsmen per oar. With the ability to model warships in computer programs that take into account the properties of wood and effects of waves, we can learn even more about construction and operations. Such a project is now underway through student research at the Maritime Studies Program, East Carolina University.

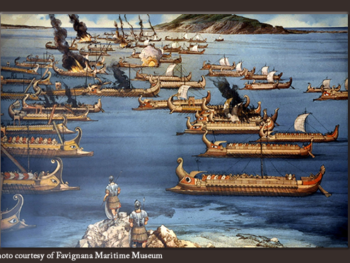

Read More Tactical formations varied due to circumstance, objectives, and the tactical armament utilized. At Ecnomus in 256 BCE, for example, the Romans warships equipped with the corvus had appropriate formations for tactical operations. In the front, the Roman’s formed a wedge formation: a line of warships trailing back from the two largest lead warships, and finally a dingle line of warships to form the base “, so that when these ships had taken their places the resulting form of the whole was a triangle.” Polybius, I.26.7.13-14 (Paton, W. R., 1954, Loeb). Behind this giant ‘spear head’ the Romans placed the horse transports to ensure maximum protection. The final formation was a single line of ships behind the horse transports that was wider than forward formation. The Carthaginians, who favored ramming tactics, countered with three quarters of their fleet in a single line that extended out to sea as their right wing. On the left wing the other one quarter of their fleet was drawn up to form an angle to the main line. A different set of tactics was favored by these antagonists at the Battle of the Egadi Island in 241 BCE. No longer equipped with the corvus, the Roman fleet opted for a direct full-frontal ramming assault. Per usual, and with little time to react, the Carthaginians offered the same tactical formation. “When [Gaius Lutatius] saw the Carthaginian ships under full sail he at once got under weigh,…he brought his fleet into a single line with their prows to the enemy…The Carthaginians, seeing that the Romans were intercepting their crossing, lowered their masts and cheering each other on in each ship closed with the enemy. The Carthginians, seeing that the Romans were intercepting their crossing, lowered their masts and cheering each other on in each ship closed with the enemy.” Polybius, I.60.9-61.1 (Paton, W. R., 1954, Loeb). After the initial head-to-head ramming to open the conflict, which undoubtedly disabled some ships, the conflict continued with attempts to ram enemy hulls that resulted in the sinking of over 50 Carthaginian warships. Archaeological evidence from the Battle of the Egadi Island archaeological site supports several aspects of naval warfare in the 3rd century BCE that are attested to in the ancient sources. As more evidence comes to us from this site, further light will be cast on the operation of warships both in battle, and in routine transit operations. The Battle of the Egadi Islands, like that of most sea battles in the First Punic War, was open-sea battles carried out away from shore where speed and maneuverability were the critical tactical features of the warships and crews. However, during the Hellenistic Period in the Eastern Mediterranean, there were a larger number and greater concentration of large port cities. Attacking these port centers was a strategic necessity and the warships’ functions relied more on size and providing large platforms; the warship designs and fleet compositions also reflect these different strategic and tactical considerations. For a thorough discussion of the Eastern Mediterranean at this time see Murray’s The Age of Titans.> Read Less

First Punic War

Initial naval engagements of First Punic War highlighted the Roman’s deficiency in training, experience, and warship operations compared to the Carthaginians. Ramming tactics had held sway for centuries and in these speed and maneuverability were essential; two benefits of excellent training, experience, and warship operations. Ramming tactics, both frontal and blows to hulls are supported by finds from the Battle of the Egadi islands. One of the misconceptions perputated by popular works is that the Romans typically utilized boarding bridges to “simulate” land battles at sea. The short-lived corvus was developed by the Romans and employed by 260 BCE in naval engagements with Carthaginians. This device was used to augment ramming tactics, typically after the initial clash. In effect it was a boarding bridge that affixed to the deck of an enemy ship by means of a large spike. Not only did this nullify the speed and maneuverability advantages of the Carthaginians, it allowed ships to be captured with little damage. As Carthaginians increased vessel speed and refined their ramming tactics, as did the Romans, the corvus was rendered ineffective and fell out of use after 250 BCE in favor of ramming tactics. Afterwards the breif experiment of the corvus was forever abandoned; the Romans continued to utilize ramming tactics augmented with projectile weapons that were the common suite of tactics in the ancient Mediterranean through the remainder of the war and the following centuries.

Initial naval engagements of First Punic War highlighted the Roman’s deficiency in training, experience, and warship operations compared to the Carthaginians. Ramming tactics had held sway for centuries and in these speed and maneuverability were essential; two benefits of excellent training, experience, and warship operations. Ramming tactics, both frontal and blows to hulls are supported by finds from the Battle of the Egadi islands. One of the misconceptions perputated by popular works is that the Romans typically utilized boarding bridges to “simulate” land battles at sea. The short-lived corvus was developed by the Romans and employed by 260 BCE in naval engagements with Carthaginians. This device was used to augment ramming tactics, typically after the initial clash. In effect it was a boarding bridge that affixed to the deck of an enemy ship by means of a large spike. Not only did this nullify the speed and maneuverability advantages of the Carthaginians, it allowed ships to be captured with little damage. As Carthaginians increased vessel speed and refined their ramming tactics, as did the Romans, the corvus was rendered ineffective and fell out of use after 250 BCE in favor of ramming tactics. Afterwards the breif experiment of the corvus was forever abandoned; the Romans continued to utilize ramming tactics augmented with projectile weapons that were the common suite of tactics in the ancient Mediterranean through the remainder of the war and the following centuries.Formations and Tactical Considerations

Read More A notion that any vessel that operated at sea, particularly with numerous individuals onboard, in conflict situations, and by both oar and sail propulsion, did so without significant equipment and stores, as well as some ballast, is contrary to any basic understanding of ship operations. Ships’ tools, arms (ship and personal), containers, and personal equipment must be taken into any realistic analysis. Metal fasteners, lead sheathing, rigging gear, anchors, equipment, weapons, crew items and possibly galley structures are commonly known to be on ancient merchantmen, and evidence from the Egadi islands indicates this was true for warships as well. This is not surprising to maritime archaeologists as the necessities of operating all sea-going vessels require basic considerations. Ancient warships conducted the overwhelming majority of their voyages under sail propulsion. For any sailed vessel ballast was mandatory for to sail effectively, a feature noted in Renaissance galleys, particularly for long and narrow vessels that had little extended keel. The numerous stones associated with the Egadi warships attest to this, and those tested have shown to come from North Africa. All vessels carry weight in addition to their hulls when in operation at sea. Consequently, when a warship’s hold was flooded, thus loosing buoyancy from displacement, the wooden elements of the hull had less ability to carry any additional weight. Warships performed diverse functions and missions throughout the 5th century B.C.E. – 3rd century C.E. and there was no standard or absolute manifest of items carried on board, a factor that directly affected their depositional fate. In the specific event of the Battle of the Egadi Islands, the Carthaginians sailed their warships loaded with supplies to the Egadi Islands, on a rough weather day, and were sailing in this manner when the Romans sprang their ambush. This over-laden condition placed the Carthaginian warships at a disadvantage in their engagement with the Romans (Polyb. I.61.4-6). The armor finds and amphora dispersion in site sector PW-A support Polybius’ account of the Carthaginian ships laden with supplies and troops while sailing. Once breached by ramming attacks during the battle, warship hulls filled with water. The material within the warships raised the hulls’ overall specific gravity to a point whereby these warships were either disabled or sank: both are attested (Polyb. I.60 – 61.6; Diod. XI.24.11.2). A breach in a mortise-and-tenon hull would catastrophically weaken it to a point that ships could break in two due to the hogging and sagging forces of waves. Evidence confirms that the rams were not removed from the hulls, but sank while attached to the warships. Warships, like all other ships and boats, had numerous fates that were determined by factors such as hull condition, cargo, ships stores, hull integrity, and the weather at the time of the sinking event.> Read Less

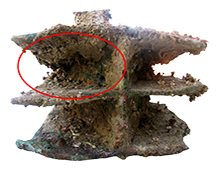

Read More The Egadi rams are currently being scanned in a project conducted by Peter Campbell, PhD candidate at the University of Southampton, through a grant by the Honor Frost Foundation. The structured 3-D light scanner operates by projecting a narrow band of light onto ram’s surface, which produces a line of illumination, or a light section, that appears distorted from other perspectives than that of the projector, and can be used to exactly reconstruct the shape of the surface. Many light sections are projected simultaneously, and as such a multitude of samples are acquired at the same time. The displacement of the stripes allows for an exact retrieval of the three-dimensional coordinates of any details on the rams surface. As part of the Ram Modeling Project initiated by Peter Campbell, and supported by a grant from the Honor Frost Foundation, a full metal analysis is being conducted by Dr. Ian Croudace. Dr. Croudace is a Professorial Research Fellow at the Ocean and Earth Science Department of the National Oceanography Centre Southampton. During the period of modeling analysis, samples were taken from each of the Egadi rams. These small samples will undergo metallurgical analysis to determine the different metals in the bronze casting and their percentage. Bronze is an alloy of Copper and Tin, with Copper usually accounting for 90% and Tin for 10%. Other trace elements are found in ancient bronze castings, and preliminary analyses indicate significant amounts of lead are present in some of the rams. The investigation will also include lead-isotope analysis in an effort to determine the origin of the lead. Samples were taken from different areas on each ram so that it will be possible to ascertain any differences within the metal due to the casting process. This metal analysis will provide the definitive results on the ram castings. In an effort to examine surface corrosion, X-ray fluorescence was chosen as a non-destructive method to provide rapid elemental composition of two bronze artifacts for analysis in 2011. Peter Campbell and a team of researchers analyzed surfaces of a bronze helmet and the Egadi 3 ram. The results suggest that the two artifacts were created using two different casting methods. After being exposed to the same site formation processes, corrosion products should be similar; however, only 60% of the elements present are shared by both and in vastly different concentrations. Another important result was that the interior of the Egadi 3 ram was exposed to corrosion for a shorter time than the exterior, due to the interior of ram being filled with the wood when the warship sank. A number of trace elements are present, but four in particular are of interest; P, Bi, S, and Fe. P is found in both the ram and helmet in amount around 1% or less. The presence of phosphorus in the Athlit ram was taken to mean it was used as a degassing agent, likely derived from bone powder. Bi is absent from the helmet but is present in ram. As an element that segregates, Bi can indicate a low-quality casting. Bronze is resistant to oxidation in water due to a quick developing patina, first of copper sulfate (CuS) followed by copper carbonate. In the helmet, S is present, but it is absent in the ram. This could indicate that the time between casting and deposition into the sea was small and the ram was rushed into service. The rear port side of the ram has a far higher Fe content than the rest of the artifact. – Peter Campbell. > Read Less

The 3D scans and metal compositional data will be used by Ship Science to make a finite element analysis, which identifies the stress load as it is spread over the surface of the ram. The scanner rapidly maps the three-dimensional features to sub-millimeter accuracy without any impact on the artifacts themselves. The scanner produces three-dimensional image that can be rotated and examined from any angle, can be measured to a fraction of a millimeter, revealing inscriptions or decorative details that are invisible to the naked eye. The next step will be to cast a 1/4 scale bronze replica and, using digital load cells and stress indicators, ram it into various hull reconstructions and other bronze pieces at a crash test facility. This data will be inserted into digital ship science models to see how water drag, etc, would influence the ram during ramming. All together this should provide functional data on the rams that will be compared to the anchor and hull conclusions in order to draw broad conclusions about technological innovation and change.

The 3D scans and metal compositional data will be used by Ship Science to make a finite element analysis, which identifies the stress load as it is spread over the surface of the ram. The scanner rapidly maps the three-dimensional features to sub-millimeter accuracy without any impact on the artifacts themselves. The scanner produces three-dimensional image that can be rotated and examined from any angle, can be measured to a fraction of a millimeter, revealing inscriptions or decorative details that are invisible to the naked eye. The next step will be to cast a 1/4 scale bronze replica and, using digital load cells and stress indicators, ram it into various hull reconstructions and other bronze pieces at a crash test facility. This data will be inserted into digital ship science models to see how water drag, etc, would influence the ram during ramming. All together this should provide functional data on the rams that will be compared to the anchor and hull conclusions in order to draw broad conclusions about technological innovation and change.Metal Analysis: The Egadi Artifacts

Surface Corrosion

Read More Unfortunately, warship studies has been largely based on iconography. The primary works on ancient warships feature large sections of iconographic collections coupled with ever more specific interpretations of the features represented. Much of the scholarship in the later 20th century relied heavily on iconography and evolved to treat representations as near ‘photographic’ records. Hence, detailed construction and design characteristics were hypothesized on the most tenuous interpretations of imagery and models. This was not the case in earlier research when the pitfalls of iconography were recognized. There are plenty of pictures of the ships on painted vases and in frescos and mosaics, and figures of them on reliefs and coins and gems and works of art of every class; for they were constantly in favour with the artists of antiquity. But these works of art must all be taken at a discount. In dealing with so large a subject as a ship, an ancient artist would seize upon some characteristics, and give prominence to these by suppressing other features; and then would modify the whole design to suit the space at his disposal. Moreover, the treatment would vary with the form of art, painters and sculptors seeing things from different points of view; and it would vary also with the period, as art went through its phases. So, works of art may easily be taken to imply a difference in the ships themselves, when the difference is only in the mode of representing them. Iconography on rams provides several insights into the study of the rams and the naval fleets. The matching sets of iconography/epigraphy indicate different building programs. The iconography has parallels to other institutional works that speak to representation of state and association with deities. As new ram discoveries are made, it will be interesting to see if grouping trends continue and if there are indeed Carthaginian depictions on any of the finds. Other molded decorative elements were included in the ram’s casting. The sole decorative elements on Egadi 1 are small rosettes cast on its fin plates. Like many state-manufactured items requiring a large investment, the Egadi rams display decorative features, albeit to varying degrees. A decorative feature present on all is the stylized shape of their fins. Unlike the cast sword handles on the fin plates of the Athlit and Acqualadroni rams that depict each fin as the blade of a sword, the Egadi fins come together at the fin plates to form a shape akin to a trident. Tridents are commonly depicted in Greco-Roman antiquity, usually associated with Poseidon/Neptune. Although less is known of the iconography associated with Punic sea dieties, it seems the trident was familiar at Carthage by the 3rd century B.C. Winged Victories are cast on the upper cowl nosings of Egadi 4 and 6; both face to their right dressed in an ankle-length gown, and carry a laurel crown in their right hand, with a palm frond in their left. C. Hallett and T. Hölscher note that crowns and palm branches were introduced at Rome for victors in 293 B.C (see Livy 10.47.3) and the Victory motif on the two rams is similar to that on Roman didrachms minted between 265 and 241 B.C. The Egadi 7 ram has a warrior head wearing a Montefortino helmet emerging from the upper cowl nosing, and its cheekpieces are identical to those found inside Egadi 6; the warrior head may be Roma personified, Minerva, or simply a soldier (identification is difficult as it appears the face was damaged in a purposeful fashion). Atop the helmet are three feathers attached to a ring sitting on its upper dome, a configuration described by Polybius. Given the problems inherent in the use of iconography, good archaeological research will place this form of evidence low in the hierarchy. The great advances in excavating and studying ancient merchant ships has demonstrated the severely limited use of iconography in understanding ship design, ship construction, and ship operation. Iconographic evidence is not to be ignored, as it can pose interesting questions and possibly provide limited, speculative information unavailable elsewhere. However, conclusive arguments can never be founded on primarily iconography as evidence. As the extant remains of warships increases the reliance on iconography is reduced and relegated to its appropriate position in the hierarchy of evidence.> Read Less

![]() Iconography defined here consists of representations of warships, fleets, and warship rams in sculpture, coins, reliefs, paintings, and models. There are a multitude of caveats involved in the interpretation of iconographic material, as well as a multitude of constraints under which the artist operated which directly affect the veracity of the final representation. Varying degrees of artistic competence, the specific nature of artistic intention, the utilized medium, the circumscribed area within which the representation was depicted, the nature, cost and access to the employed medium, the intrinsic desire for realistic depiction versus the symbolic intent of approximation, the availability of objects and models for the artist to consciously emulate (assuming an intent to depict realistically), the use of anachronism and symbolism – all of these elements need to be taken into consideration when evaluating the iconographic element, and basing further research upon it.

Iconography defined here consists of representations of warships, fleets, and warship rams in sculpture, coins, reliefs, paintings, and models. There are a multitude of caveats involved in the interpretation of iconographic material, as well as a multitude of constraints under which the artist operated which directly affect the veracity of the final representation. Varying degrees of artistic competence, the specific nature of artistic intention, the utilized medium, the circumscribed area within which the representation was depicted, the nature, cost and access to the employed medium, the intrinsic desire for realistic depiction versus the symbolic intent of approximation, the availability of objects and models for the artist to consciously emulate (assuming an intent to depict realistically), the use of anachronism and symbolism – all of these elements need to be taken into consideration when evaluating the iconographic element, and basing further research upon it.

![]()

(C. Torr 1895, Ancient Ships, Cambridge University Press, p. viii)Iconography on Rams

![]()

Conclusion Regarding Iconographic Evidence

Read More The Greeks, at a signal, brought the sterns of their ships together into a small compass, and turned their prows on every side towards the barbarians; after which, at a second signal, although inclosed within a narrow space, and closely pressed upon by the foe, yet they fell bravely to work, and captured thirty ships of the barbarians, at the same time taking prisoner Philaon, the son of Chersis, and brother of Gorgus king of Salamis, a man of much repute in the fleet. (The Histories, Book 8) The History of Herodotus (full text) The Corinthians, however, would not listen to any of these proposals, but as soon as their ships were manned and their allies were at hand, they sent a herald in advance to delcare war against the Corcyaeans; then setting off with seventy-five ships and two thousand hoplites, they sailed fo Epidamnus to give battle to the Corcyraeans. (History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 1.29) History of the Peloponnesian War (full text) Next year Gaius Atilius Regulus the Roman Consul, while anchored off Tyndaris, caught sight of the Carthaginian fleet sailing past in disorder. Ordering his crews to follow the leaders, he dashed out before the rest with ten ships sailing together. The Carthaginians, observing that some of the enemy were still embarking, and some just getting under weigh, while those in the van had much outstripped the others, turned and met them. Surrounding them they sunk the rest of the ten, and came very near to taking the admiral’s ship with its crew. However, as it was well manned and swift, it foiled their expectation and got out of danger. (The Histories, I.25.1-3) Polybius: The Histories (full text) Rather than the modern notion of historical accuracy and attempting to identify biases in order to account for them in interpretations, ancient historians had other, equally valid objectives. These often included pleasing their benefactor, championing a cause, or promoting themselves. Additionally, with travel and access to truly ‘eyewitness’ material greatly more difficult in the ancient world, it is often unclear as to the sources or how they were actually used by ancient historians, albeit their claims of faithful accuracy. Moreover, as there are relatively few historians for each period, there is little ability to discern what events were not chronicled, and no comparative material for the details of those that were reported. Even for reported events, we are left with what one particular individual found worthy of noting. We are left with a spotty record, both in events and in specific details, none of which is sufficient to proffer sound hypotheses on warship construction or ram manufacture. However, like inscriptions, historical accounts can provide some details to the hypotheses founded in direct evidence.> Read Less Herodotus – Persian Wars

Herodotus – Persian Wars Thucydides – Peloponnesian War

Thucydides – Peloponnesian War Polybius – Punic Wars

Polybius – Punic WarsAccuracy of Historical Accounts

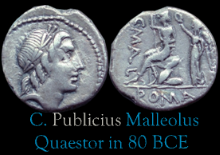

Read More The information such inscriptions provide work well in conjunction with direct archaeological evidence to better understand the overall nature of warship outfitting and operation. However, it must always be limited to the culture and time period from which it is derived, and not freely applied across cultures and centuries. Another type of inscription evidence is derived from commemorative dedications for naval victories or feats. Typically, these were in connection to the exploits of a single commander, such as the columna rostrata that was an eulogium of Gaius Duilius’ naval victory over the Carthaginians in 260 BCE. Inherent information from these inscriptions is limited to the players and the place of the event, an indication of numbers, and perhaps a general detail of the events outcome. However, technical and detailed descriptive information is rarely included. Moreover, the purpose of such inscriptions is not administrative, thus a necessity to record basic factual information, rather they served propaganda and promotional needs. Hence the information must be taken with this caveat, and its reliability is not as great as more pragmatic lists or inventories. Some warship rams themselves also harbor inscriptions. Below are examples of a few of these and translations of these inscriptions. Dr. Johnathan Prag (University of Oxford) translation Preliminary translation by Dr. Tommaso Gnoli, University of Bologna “We pray to Baal that this ram will go into the enemy ship and make a big hole.” -Archaeology Magazine 2012 Advanced translation by Dr. Philip Schmitz, Eastern Michigan University “…wrath O Baal our out upon him; opposite Greece may a lightning storm and its waters pull our enemy down [n…]” Quaestors sometime between 255-42 B.C.E.? Quaestors had a significant role in fleet construction. Dr. Jonathan Prag, University of Oxford, Dr. Francesca Oliveri, Soprintendenza del Mare, Dr. Paul Iverson, Case Western Reserve University “E · QUAISTOR · PROBAVET” Dr. Jonathan Pra (University of Oxford) translation > Read LessRam Inscriptions

Egadi 1 Ram Inscription

Egadi 3 Ram Inscription

Egadi 4 & 6 Ram Inscriptions

C(aio) Paperio TI(berii) F(ilii) Q(uaestores) P(opuli) or (uplici)

C(aio) Paperio TI(berii) F(ilii) Q(uaestores) P(opuli) or (uplici)

M(arco) Populicio L(uci) F(ilii)

No command functions can be postulated.Egadi 7 Ram Inscription

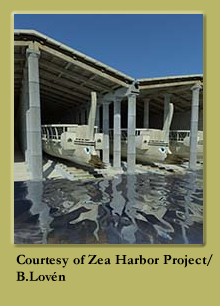

Read More A most unique form of indirect archaeological evidence comes from the Actium War Monument in Greece. This monument was ordered constructed by Augustus to commemorate his victory over Marc Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. The location is on Augustus’ campsite prior to the naval engagement. Among the features of this large monument are sockets which have an outline shape that closely resembles that of the Athlit ram. Dr. William Murray has spearheaded the study of Actium monument, and decades of study have led him to conclude that these sockets held the actual rams of captured warships from the larger classes in Antony’s fleet. Currently, Dr. Murray is modeling the monument in sub-centimetric detail in order to then model the rams that fit within the sockets. These ram models will provide an indication of warship construction in a similar, but less precise manner, as the actual ram finds have provided for their warships. Read More About The Actium War Monument & Dr. Murray’s Work The primary source of indirect evidence is from shipsheds. Shipsheds were facilities that held warships when they were hauled out, the object being to provide a place protected from sun and weather where they could be repaired, refitted, and maintained, as well as safely stored for periods of time. Keeping a warship out of the sea for periods lengthened its service life. Generally, shipsheds consisted of stone ramps from the sea with a roof held aloft by columns running between each shed. As with sunken vessels, teredo worms attack ships hulls when in service. To combat this problem ancient shipwrights sheathed the hulls of their merchantmen in lead; the pitch used in the process had the added benefit of providing some protection from direct water contact. When a merchantman’s hull required repair, it was hauled out to perform the necessary work and then put back into service. With merchantmen, time was money. Warships operated on a different schedule whereby their deployment was not as regular; hence there were longer intervals where they were not being used. Given the large investment in a warship and the requirement to have it functional when deployed, they could not be left to the damaging effects of water and teredo – hauling out addressed some of this. Dry rot remained a vital issue to combat even after hauling out, but one that could be better managed. The shipshed in which the warships were stored provide us with one basic piece of information – they fit inside. There are many elaborate hypotheses regarding how they fit, what certain stone marks or shape in the sheds indicate, and even how many fit inside each shed. However, there is no direct evidence for how warships fit into shipsheds. Not only did these shipsheds house the warships, but they were also work spaces for the shipwrights and crews that serviced them. Without adequate space for individuals to work, remove timbers, swing tools, erect braces, etc. these shipsheds would be useless. Hence we have what is essentially a garage. Looking at an empty garage one knows that one, or possibly more, cars could fit inside along with tools and room to work. However, how big was the actual car(s) that were inside? All one has is a maximum limit. The same holds for shipsheds, where we are left with hypothesizing on maximum size limits of the warships that fit within them. What shipsheds cannot provide is exactly the warship size below this maximum limit. With the increase in direct evidence for warships, and thus now a better-founded estimation of warship sizes, the more logical exercise is to examine the situation of these warships in the shipsheds towards an understanding of the work room and storage that are thus afforded. Some hypotheses have the warships’ widths spanning the entire distances between the supporting columns. This concept has the problem of not allowing room for repair, maintenance, and storage of warship equipment. Even under this hypothesis, the sheds are typically too narrow to house the hypothesized ‘large’ warships: the 5-10’s. Those at the military in Carthage are particularly narrow, the shed itself around 4.5 m. It is interesting to note that the shipsheds at Carthage, like many others, would house the size of the Egadi warships. As with direct archaeological evidence, it is important to maintain the context for the use of indirect evidence. For example, it is improper to use shipsheds built in the 5th century BCE and used until the 4th century to assess the maximum widths of warhsips in the 1st century BCE. Likewise, shipsheds built in Greece have no more inherent association to those in Carthage, any more then is found in other architecture. For more information on shipsheds and the Actium War Memorial browse the following links and publications: > Read Less Indirect archaeological evidence is available for the study of ancient warships. This class of data is considered indirect in that it does not include the physical remains of warships, rather something that was associated with their use.

Indirect archaeological evidence is available for the study of ancient warships. This class of data is considered indirect in that it does not include the physical remains of warships, rather something that was associated with their use.

Actium War Monument

Shipsheds – What was their purpose?

Shipshed Sizes & Warship Sizes

Additional Resources

The site of a major naval battle between Roman and Carthage during the First Punic War; the first ancient naval battlegrounds to be found by archaeologists

The site of a major naval battle between Roman and Carthage during the First Punic War; the first ancient naval battlegrounds to be found by archaeologists

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Bronze helmets with a Celtic origin found at the site of the Battle of the Aegates

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands

Ancient warship ram from the First Punic War found off the Egadi islands